Nairobi, Silicon Valley of Development

The mist is still clinging to everything at this early morning hour of one of Nairobi’s chilliest Augusts when we arrive at Kangemi slum to meet Maria Springer, one of the founders of Livelyhoods.

It just took us 20 meters to leave the rich mansions of Springvalley and Hillview, to cross the highway, and to arrive at what the UN now call “informal settlements,” the home of 50% of Kenya’s urban population.

Maria, American native of 25 years, with a shine on her face is waiting for us in front of iSmart, the new shop her organization opened last Friday in the neighborhood, which now serves 650,000 people.

Behind her young age and her genuine face is hidden a strong determination to provide jobs to the youth of Nairobi’s slums.

¨My story is intimately linked to Kenya. My aunt and uncle used to live here for years when I was a kid. At that moment, they hosted a young boy from the street and raised him. We started writing to each other and when I arrived here, I decided I wanted to have a positive impact on his reality, and the best tool was to provide them with jobs to keep them off the street.¨

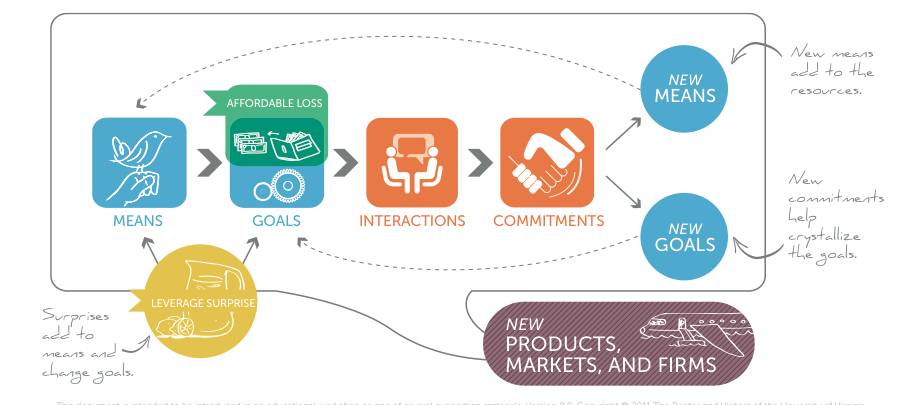

So Maria decided to hire young professionals as sales force to reach the last mile between private companies and hard-to-reach potential customers.

So Maria decided to hire young professionals as sales force to reach the last mile between private companies and hard-to-reach potential customers.

200 salesmen have already been hired from Livelyhoods in order to distribute high quality and ecologically respectful products like solar lamps, cooking stoves or female hygiene products to the base of the pyramid.

The story of Maria is not exceptional in Kenya’s capital. The local ecosystem has become an extremely favorable soil for many entrepreneurs, mostly expatriates willing to set up sustainable organizations with a social impact.

Kenya is the new Far West – the next Frontier. The climate is good, the infrastructure relatively developed in the Sub-Saharan context and the government is stable enough to let private ventures develop pretty freely, at least during the first years.

The mobile penetration of 75% and the growing internet economy makes it possible to reach customers all around the country. Kenya’s population is well trained, and access to the Mombasa harbor makes any international trade quite convenient.

However, unlike in Europe or the US, there are still core needs to be addressed. Many people here lack access to the things they need most: farmers to markets in which to sell products, students to quality education, and citizens to vital information. The social issues are extremely present with a country of 46% living under the poverty line and 3.9 million slum inhabitants.

Plenty needs to be done. And Nairobi knows it, as the diplomatic and humanitarian capital of East Africa.

Thousands of staff of United Nations agencies and International NGOs are dealing with surrounding humanitarian crises, such as the Somalia situation and the 500,000 refugees in Dadaab, Africa’s largest refugee camp in the north of the country.

And yet, at the difference of the traditional cooperation model, a new generation of entrepreneurs is trying to tackle social issues like unemployment, education, and healthcare in a sustainable way.

I’m not talking so much about donors and beneficiaries, but more about clients and investors. The entrepreneurs focus here on answering a market need: farmers who want to produce in higher quantities and qualities, private companies who reach new customers or find employees through a social or environmental approach, employing marginalized youth, distributing ecologically respectful products, providing services to excluded population.

Kenya has become a haven for social business. As Samir, 23 from NY says, “Here you can actually start a project and see it grow. If you can make it in Kenya, you can make it anywhere.¨ His organization SunCulture is developing an innovative solar powered irrigation system allowing medium sized farmers to diversify their production and multiply their income by ten in one year. Their target is simply the 30 million farmers living in Kenya representing 24% of the country’s GDP. There is massive potential, both here and in neighboring countries. (See SunCulture’s elevator pitch videos here and here.)

And this kind of potential offers an exciting perspective of bustling business opportunities for any young and committed professional.

The next generation is flocking into Nairobi aspiring to merge career and meaning: the thrill of setting up their own project in a fascinating environment of an emerging country reaching a tipping point, and the satisfaction of making a positive impact on their environment.

The sons and daughters of the Wall Street Generation are now startupers in East Africa. And some may even compare the city to an exotic playground for young entrepreneurs as the polemic articles from Jonathan Kalan underlined.

And as Lino Carcoforo, the young investor from Innovation for Africa, says: “We will have to see from all these initiatives which actually gather the necessary business skills to make it to the other level.”

Yet, even if the perennity of some of the existing ventures is still to be proven, one can’t deny the vibrant atmosphere of the city where business incubators, start-up competitions, and early stage investors gather. And Kenyan entrepreneurs, sometimes lacking the visibility of their international colleagues, are also emerging and leading some of the country’s most promising ventures. Let’s hope this current hype will prove impactful in the coming years and change at least the vision most still have of our original continent.

By: Aurelie Salvaire